Nine to Twelve

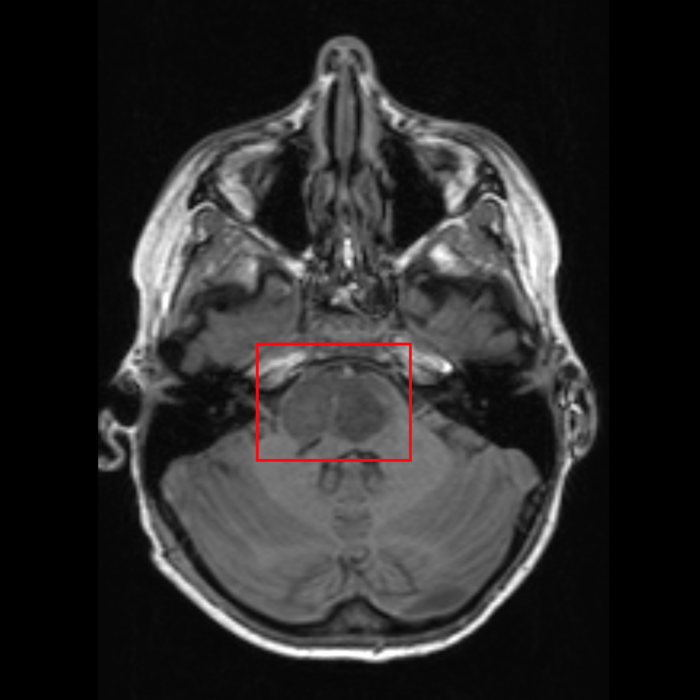

Asher’s MRI went as planned that morning, and before they brought him back to his hospital room, Leah and I were pulled into a consultation room with the neurosurgeon, an oncologist, and a couple of nurses. I don’t recall all of the exact words that were said. They explained the initial diagnosis, and filled in the rest as answers to our questions. We were told that the tumor in Asher’s brain is called a diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG). Tje diffuse nature of the tumor means the bad cells are mixed in with healthy cells, so it cannot be removed surgically. It is located in the pons of the brain, which controls the major functions of the body that keep us alive like breathing and heart rate, making it risky to operate on. DIPG tumors are typically aggressive to the point of being considered stage four. The standard of treatment is radiation therapy, which he will need to receive at St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis. There are clinical trial options available. We had to decide whether or not for them to perform a biopsy, the first of many medical decisions we would need to make along the way.

There is no cure.

The chance of survival is near zero.

The median survival range is nine to twelve months.

Beyond the standard of care and the hope of clinical trials, there will be nothing else that can be done for medical treatment.

Nothing can prepare you to take a blow like that. The world stopped.

The one question I can explicitly remember is when my wife asked about what we would say if Asher asked if he was going to die. The oncologist responded, that their response is always, “We always tell the children, ‘We hope not.’ Everything that we do is built on hope.”

After the medical team had answered as many of our questions as they could in between our tears, the left the room to give us a moment. Before the last nurse stepped out, I asked if she would send in our pastor and friend who had been waiting back in the hospital room. We held each other, and sobbed uncontrollably. When our pastor walked in a few moments later, we just looked at him, and he knew. He sat down between us, hooked us both with his arms, and wept with us in broken-hearted solidarity as if it were one of his own children. In between the sobs, we managed to spell out the details. It wasn’t long before they were wheeling Asher back to his hospital room from his MRI. We dried our tears and walked back up the hall to see him. He was still asleep, because he had been sedated for a very lengthy MRI. I decided to leave the hospital while he was still sleeping to go tell my parents, who live nearby, the news in person. My wife’s family lives across several other states, so she would be forced to tell them all by phone. Our pastor offered to drive me, so I took him up on the offer, and we made the forty-five minute drive to my parent’s house.

Telling my parents that their first grandson’s brain tumor was malignant would likely not live longer than about a year was easily one of the most difficult things I’ve ever had to do. Watching their faces as the grief and the shock set in was shattering. I took them to a back bedroom, away from my daughter, nieces, and nephew, so that they would be free to take it in and grieve. My sister showed up not too long after I broke the news to my parents.

Leah’s task wasn’t any easier over the next couple of days as she reached out to her family that lives out of state to deliver the news. Perhaps it was even a little harder because none of them could reach through the phone to hold her. Video calling technology is a wonderful thing, but my heart was broken as I watched members of her family take in the devastating news, and look so helpless for not be able to do anything to bring comfort to my wife.

“Don’t Google it” was a common piece of advice we gave out for a while. It’s one thing to know that a disease like DIPG is likely going to take your loved one. It’s another to know that, before it does, it will take nearly everything from them, while leaving them fully aware of everything that’s happening to them.

By the time I had returned to the hospital, someone had already spent some time with Asher, showing him a picture of the tumor in his MRI. In true Asher form, he had already named his DIPG tumor “Dippy,” and loved to point out that it was “shaped like a butt.”

We have a closely-knit church community, but we were careful about how we discussed the news of what was happening to us. We didn’t publicly discuss the specific timeline we were given, because we didn’t know for sure what would ultimately happen. God could heal him. God could choose to be gracious to the many families suffering in this way by providing a cure. To that end, one of our pastors carefully worded a statement that provided enough direct information where people would understand the basic details and the gravity of the situation:

Thank you for praying for Asher. He was diagnosed with a brain tumor. The prognosis is not good.

He is getting the best medical care available to him locally. The Ammons family will also be travelling to St. Jude’s Hospital soon for several weeks of treatment.

However, apart from a miraculous, healing work of God, Asher’s condition is more than what human medicine can handle.

We are praying and asking the Lord for His power and might in this. We want to ask you to pray for them.

We are also working on a plan to care for them. Thanks for your patience in this. We will communicate it as soon as possible