Connecting with History

In the northeast corner of my neighborhood is a connection to the South Fork Trail of the Carolina Thread Trail network, maintained by the Catawba Lands Conservancy. It’s a nice trail that follows the South Fork River southward for a little over two miles.

During my first stroll on the trail, I had made it about halfway when a bench next to the river caught my eye, and I decided to sit for a moment to rest, and watch the river. As I drew closer, I noticed that the bench was centered on top of large, old blocks, and as I looked out across the water, I saw more of the same blocks, forming at least two bridge piers.

Old Bridge in the Summer

Old Bridge in the Winter

The bridge, or what was left of it, was clearly very old, at least for America. But how old was it? What happened to it? I have lived in Gaston County my entire life, and I had never heard of it. I was fascinated, and very curious, to say the least.

Back home, I found that the Carolina Thread Trail website marks that site as a historical attraction, so within a day of contacting their team, I had the primary piece of an intriguing story that set my course for researching the history of this old bridge.

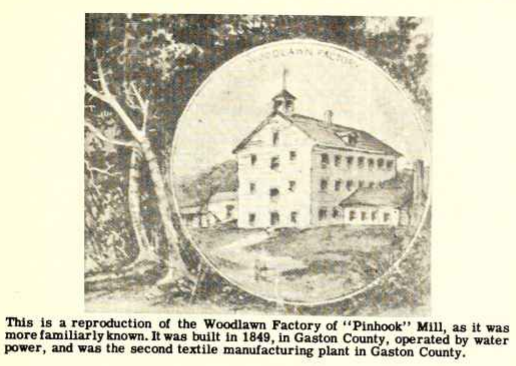

Gaston County’s colorful past is rooted in textiles. The second cotton mill in Gaston County, built in 1852 by Caleb John Lineberger, was a small facility called Woodlawn Factory, located on the west bank of the South Fork River, in modern day Lowell. Over time, Woodlawn Factory was better known as “Pinhook Mill,” nicknamed as such because, it is said, employees would fish from the windows of the mill using brass pins that, when bent, apparently made excellent fishing hooks.

With the advent of The American Civil War in 1861, cotton mills were an increasingly important asset. Robert A. Ragan says in his book A Textile Heritage of Gaston County, North Carolina, that in the early days of the war, there were about 50 cotton mills in North Carolina, operating at full capacity, around the clock. Women, children, and slaves were now the primary demographic of the mill worker, as most of the men had left to join the army. Pinhook Mill’s looms and spindles were dedicated to producing colored cloth, and yarn, much of which was destined for the Confederate military.

General Sherman’s “March to the Sea” of 1864 devastated the South, and, towards the end of the war, and for some time afterwards, bandits and small detachments of troops were sometimes known to raid, and often destroy southern manufacturing facilities.

The superintendent of Pinhook around this time was a man, about forty years old, named William Sahms (1). William was a German who immigrated to the United States with his family around 1832, growing up in Pennsylvania.

An 1958 article from the Gaston Gazette gives details taken from the diary of Jacob Froneberger, a Dallas, NC resident and business owner during the same time period, who gave an account of the incident at the center of this story (added emphasis is mine):

The War Between the States terminated when Gen. Lee signed the surrender documents at Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia, at 2 o’clock on Sunday, April 9, 1865.

According to Jacob Froneberger’s diary, several companies came through and camped at Dallas. While some were Federal solders, others were nothing but desperados.

One company of these went down the river to Solomon Hoffman’s grist mill at Spencer Mountain, dismounted their horses, went in the mill and took all the flour and meal they could take with them, and the rest was poured out on the ground. They mounted their horses and went on down the river to Lineberger’s Mill.

At that time, the superintendent was a German from Pennsylvania by the name of Bill Sahams. Mr. Sahams, being on duty, heard the noise and went outside and called to them, “Who’s there?” “Yankees” was the answer. Mr. Sahams then said, “I am, too, come on in.” One of the soldiers recognized his voice and said, “Well, if it ain’t old Bill Sahams.” This proved to be a man from his former neighborhood in Pennsylvania. The Yankees told him what they had come for; but he persuaded them not to burn the mill, telling them if they did he would be out of a job and they would not be any better off. They left without burning the mill but did burn the bridge across the river.

Even by itself, this would stand as a rich story which more than satisfied my curiosity about the remains of that old bridge. But the choice to not burn down the mill that day had effects that rippled throughout our local history. Pinhook survived for nearly another twenty years, through some of the worst economic times experienced by the South. Ragan explains the legacy left by Pinhook:

Little Pinhook was largely responsible for the beginning of Gaston County’s great industry, and from it emerged two young men who built many mills and played outstanding parts in building the combed cotton yarn industry of the South.

The first was George Alexander Gray (1851 – 1912) who began his career at the Pinhook in 1861 at the age of ten. He swept floors for a few cents a day and by sheer will and determination advanced to the superintendency of the mill eleven years later. Continuing his self-made career, and with firsthand knowledge of textile machinery and cotton manufacturing methods, he helped start Charlotte’s first cotton mill in 1878 and the first mill at McAdenville in 1881. In 1887 he moved to Gastonia to join a group in founding its first cotton factory and soon thereafter became a partner in the mill-building activities of George Ragan and John Love. He stands with the best of the textile pioneers.

The second was Abel Caleb Lineberger (1859 – 1947), a son of Caleb John Lineberger, who began his career at Pinhook Mill in 1880 at the age of twenty-two. In 1883 or 1884, he went to the Tuckaseege Manufacturing Company, where he continued to learn lessons in cotton manufacturing, and soon became superintendent there. He then went to Belmont in 1902, where he became associated with Robert and Pinckney Stowe, and together they built and operated a series of combed yarn mills that eventually numbered twenty. Abel Lineberger and his father spent a century bringing the South an industry to balance its agriculture. The Lineberger name stands at the top of any list of pioneers who developed Gaston County into a world textile center.

A 1962 publication by the Gastonia Chamber of Commerce states that Gaston County had developed into “the foremost textile manufacturing county in the nation” having more active spindles and consuming more cotton than any other county in the United States, and employing 29,000 people. By the mid 1970’s, about 70% of the jobs in Gaston County were in or directly related to textiles and manufacturing. According to textilehistory.org, at it’s peak “Gaston County may have had the largest concentration of combed-yarn sales mills of any area in the U.S. in addition to vertical mills, dye houses and machinery manufacturers.”

I find it stunning to be able to trace part of the foundation of the once massive textiles industry of Gaston County’s back to this one moment in time when a German immigrant, living hundreds of miles from where he grew up in Pennsylvania, came face to face with a former neighbor, influencing that man’s choice in what would be a history-altering decision.

Everybody, sooner or later, sits down to a banquet of consequences. - a pertinent misquote of Robert Louis Stevenson

Notes:

(1) According to census records, Sahms is the correct spelling of the surname of this individual.